Winner, animals in their environment. Grizzly leftovers, by Zack Clothier, US. A grizzly bear takes an interest in Clothier’s camera trap. Returning to the scene was challenging. Clothier bridged gushing meltwater with fallen trees, only to find his setup trashed. This was the last frame captured on the camera. Grizzlies, a sub-species of brown bears, spend up to seven months in a torpor, a light form of hibernation. Emerging in spring, they are hungry and consume a wide variety of food, including mammals. (Photo by Zack Clothier/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, rising star portfolio award. Cool time, from land time for sea bears, by Martin Gregus, Canada/Slovakia. Gregus shows polar bears in a different light as they come ashore in summer. On a hot day, two female bears cool off and play. Gregus used a drone to capture this moment. For him, the heart shape symbolises the apparent sibling affection between them and “the love we as people owe to the natural world”. He spent three weeks photographing the bears around Hudson Bay. In summer, they live mainly off their fat reserves and, with less pressure to find food, become more sociable. (Photo by Martin Gregus/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, behaviour: birds. The intimate touch, by Shane Kalyn, Canada. Ravens during a courtship display. It was midwinter, the start of the ravens’ breeding season. Kalyn lay on the frozen ground using the muted light to capture the detail of the ravens’ iridescent plumage against the contrasting snow to reveal this intimate moment when their thick black bills came together. Ravens probably mate for life. This couple exchanged gifts – moss, twigs and small stones – and preened and serenaded each other with soft warbling sounds to strengthen their relationship, or “pair bond”. (Photo by Shane Kalyn/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, plants and fungi. Rich reflections, by Justin Gilligan, Australia. A marine ranger is reflected among the seaweed. At the world’s southern-most tropical reef, Gilligan wanted to show how careful human management helps preserve this vibrant seaweed jungle. With only a 40-minute window where tide conditions were right, it took three days of trial and error before he got his image. Impacts of the climate crisis, such as increasing water temperature, are affecting the reefs. Seaweed forests support hundreds of species, capture carbon, produce oxygen and protect shorelines. (Photo by Justin Gilligan/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, behaviour: mammals. Head to head, by Stefano Unterthiner, Italy. Two Svalbard reindeer fight for control of a harem. Watching the battle, Unterthiner felt immersed in “the smell, the noise, the fatigue and the pain”. The reindeer clashed antlers until the dominant male, left, chased its rival away, securing the opportunity to breed. Reindeer are widespread around the Arctic, but this subspecies occurs only in Svalbard. Populations are affected by the climate crisis, where increased rainfall can freeze on the ground, preventing access to plants. (Photo by Stefano Unterthiner/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, behaviour: invertebrates. Spinning the cradle, by Gil Wizen, Israel/Canada. A fishing spider stretches out silk from its spinnerets to weave into its egg sac. Wizen discovered this spider under loose bark. “The action of the spinnerets reminded me of the movement of human fingers when weaving”, Wizen says. These spiders are common in wetlands and temperate forests of eastern North America. More than 750 eggs have been recorded in a single sac. Fishing spiders carry their egg sacs with them until the eggs hatch and the spiderlings disperse. (Photo by Gil Wizen/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, behaviour: amphibians and reptiles. Where the giant newts breed, by João Rodrigues, Portugal. Rodrigues is surprised by a pair of courting sharp-ribbed salamanders. It was his first chance in five years to dive in this lake, as it emerges only in winters of exceptionally heavy rainfall. He had a split second to adjust his camera settings before they swam away. Found on the Iberian Peninsula and in northern Morocco, the salamanders use their pointed ribs as weapons, piercing through their own skin and picking up poisonous secretions, then jabbing them into an attacker. (Photo by João Rodrigues/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

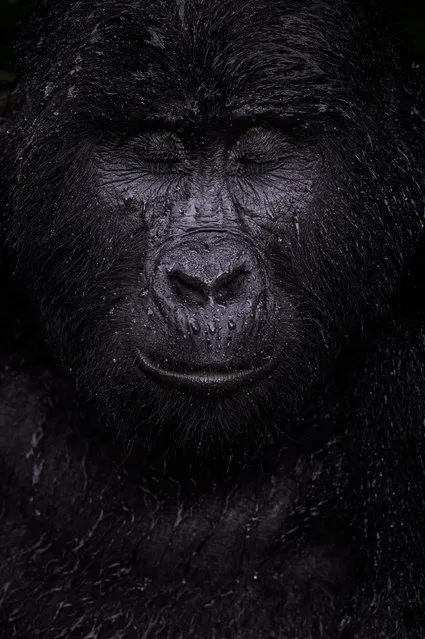

Winner, animal portraits. Reflection, by Majed Ali, Kuwait. Ali trekked for four hours to meet Kibande, an almost 40-year-old mountain gorilla. “The more we climbed, the hotter and more humid it got”, he recalls. As cooling rain began to fall, Kibande remained in the open, seeming to enjoy the shower. Mountain gorillas are a sub-species of the eastern gorilla, and are found at altitudes above 1,400 metres in two isolated populations: at the Virunga volcano and the Bwindi area. They are endangered by habitat loss, disease and poaching. (Photo by Majed Ali/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, underwater. Creation, by Laurent Ballesta, France. A trio of camouflage groupers leaves a milky cloud of eggs and sperm. For five years, Ballesta and his team returned to this lagoon, diving day and night to see the annual spawning of camouflage groupers. They were joined after dark by reef sharks hunting the fish. Spawning happens around the full moon in July, when up to 20,000 fish gather in Fakarava in a narrow, southern channel linking the lagoon with the ocean. Overfishing threatens this species, but here the fish are protected within a biosphere reserve. (Photo by Laurent Ballesta/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, portfolio award. Face-off, from Cichlids of Planet Tanganyika, by Angel Fitor, Spain. Two male cichlid fish fight over a snail shell in Lake Tanganyika. Inside the half-buried shell is a female ready to lay eggs. For three weeks, Fitor monitored the lake bed looking for such disputes. The biting and pushing lasts until the weaker fish gives way. Lake Tanganyika is home to more than 240 species of cichlid fishes. But this incredible ecosystem is under threat from chemical runoff from agriculture, sewage, and over-exploitation by the unregulated ornamental fish trade. (Photo by Angel Fitor/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, wetlands: the bigger picture. Road to ruin, by Javier Lafuente, Spain. A stark, straight line of road slices through the curves of the wetland landscape. By manoeuvring his drone and inclining the camera, Lafuente dealt with the challenges of sunlight reflected by the water and ever-changing light conditions. Dividing the wetland in two, this road was constructed in the 1980s to provide access to a beach. The tidal wetland is home to more than 100 species of birds, with ospreys and bee-eaters among many migratory visitors. (Photo by Javier Lafuente/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, oceans: the bigger picture. Nursery meltdown, by Jennifer Hayes, US. Hayes records harp seals, seal pups and the blood of birth against melting sea ice. After a storm, it took hours of searching by helicopter to find this fractured sea ice used as a birthing platform by harp seals. “It was a pulse of life that took your breath away”, she says. Every autumn, harp seals migrate south from the Arctic to their breeding grounds, delaying births until the sea ice forms. Seals depend on the ice, which means population numbers are likely to be affected by the climate crisis. (Photo by Jennifer Hayes/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, urban wildlife. The spider room, by Gil Wizen, Israel/Canada. Wizen found one of the world’s most venomous spiders, a Brazilian wandering spider, guarding its brood under his bed. Before safely moving it outdoors he photographed the human-hand-sized spider, using forced perspective to make it appear even larger. Brazilian wandering spiders roam forest floors at night in search of prey, such as frogs and cockroaches. Their toxic venom can be deadly to mammals, including humans, but it also has medicinal uses. (Photo by Gil Wizen/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, photojournalist story award. The healing touch, from community care, by Brent Stirton, South Africa. The director of the Lwiro Primate Rehabilitation Centre, in Kinshasa, cuddles a chimp orphaned by the bushmeat trade. Young chimps are given one-to-one care to ease their psychological and physical trauma. These chimps are lucky, as fewer than one in 10 orphans are rescued. Many people rely on meat from wild animals – bush meat – for protein, as well as a source of income. Many staff at the centre are survivors of military conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, photojournalism. Elephant in the room, by Adam Oswell, Australia Zoo. Visitors watch a young elephant performing underwater. Oswell was disturbed by this scene, and organisations concerned with the welfare of captive elephants say performances like this encourage unnatural behaviour. In Thailand, there are now more elephants in captivity than in the wild. With the Covid pandemic causing tourism to collapse, elephant sanctuaries are becoming overwhelmed with animals that can no longer be looked after by their owners. (Photo by Adam Oswell/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, natural artistry. Bedazzled, by Alex Mustard, UK. A ghost pipefish hides among the arms of a feather star. Mustard had always wanted to capture this image of a juvenile ghost pipefish, but usually only found darker adults on matching feather stars. His image conveys the confusion a predator would be likely to face when encountering this kaleidoscope of colour and pattern. The juvenile’s loud colours signify that it landed on the coral reef in the last 24 hours. In a day or two, its colour pattern will change, enabling it to blend in with the feather star. (Photo by Alexander Mustard/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, 15-17 years. High-flying jay, by Lasse Kurkela, Finland. A Siberian jay flies to the top of a spruce tree to stash its food. Lasse wanted to give a sense of scale in his photograph of the jay, tiny among the spruce. He used pieces of cheese to get the jays accustomed to his remotely controlled camera and to encourage them along a particular flight path. Siberian jays use old trees as larders. Their sticky saliva helps them glue food, such as seeds, berries, small rodents and insects, high up in the holes and crevices of the bark and among hanging lichens. (Photo by Heikki Kurkela/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, 11-14 years. Sunflower songbird, by Andrés Luis Dominguez Blanco, Spain. As light faded at the end of a warm May afternoon, Andrés’ attention was drawn to a warbler flitting from flower to flower. From his hide in his father’s car, he photographed the singer, “the king of its territory”. Melodious warblers are one of more than 400 species of songbird known as old world warblers, which each have a distinctive song. The song of a melodious warbler is a pleasant babbling, without the mimicked sounds that other warblers sometimes make. (Photo by Andrés Luis Dominguez/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)

Winner, 10 years and under. Dome home, by Vidyun R. Hebbar, India. Vidyun watches a tent spider as a tuk-tuk passes by. Exploring his local theme park, he found an occupied spider’s web in a gap in a wall. The tuk-tuk provided a backdrop of rainbow colours to set off the spider’s silk creation. Tent spiders are tiny – this one had legs spanning less than 15mm. They weave non-sticky, square-meshed domes, surrounded by tangled networks of threads that make it difficult for prey to escape. Instead of spinning new webs every day, the spiders repair existing ones. (Photo by Vidyun R. Hebbar/Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021)